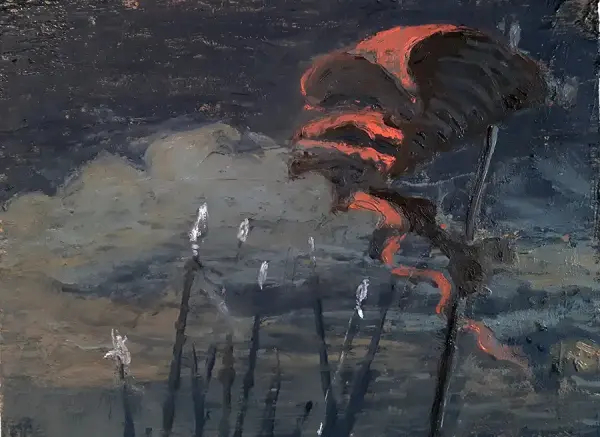

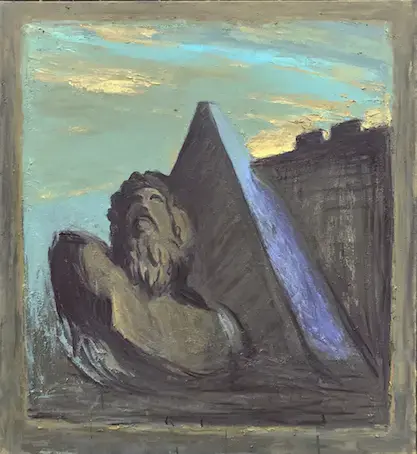

Examining our ability to see, process and recognize the visual forms of the past in a visually over-saturated and ‘post-historical’ era, Saint-Pierre’s work, with its summary paint handling, privileges perception. His approach centres on historical dislocation and perceptual ambiguity and a preoccupation with fragmentation, seriality and the metonymic function of emblematic forms. Using classical architectural and sculptural forms as a starting point, he creates hypothetical landscapes that evoke the history of painting while teetering on the edge of legibility. Read insights into François Xavier Saint-Pierre's artistic processes and exhibition development of The Spiders and the Bees in IN THE WORKS: François Xavier Saint-Pierre and the exhibition brochure .

François Xavier Saint-Pierre is a Canadian painter who received his BFA from Concordia University in Montreal, where he studied under Guido Molinari and Yves Gaucher and his MFA from the University of Waterloo. He was a finalist in the 2006 RBC Canadian Painting Competition and has participated in international residencies in the UK, in Italy, where he was an artist in residence at the French Academy in Rome, and in the middle of the Baltic Sea on a remote island with more sheep than people. He has exhibited across Canada and internationally.

David Jager is a writer and musician living in Muskoka. He was art reviewer for NOW magazine for over ten years, and did several cover features and reviews on contemporary artists for Canadian Art . He is currently a freelance curator, art writer, gallery owner and academic. He also writes rock musicals.

Capital. Oil on panel, 83 X 74 cm, 2017. (right) François Xavier Saint-Pierre, Capital in Evening Light. Oil on linen, 83 X 74 cm, 2017.